- Home

- Greg Dybec

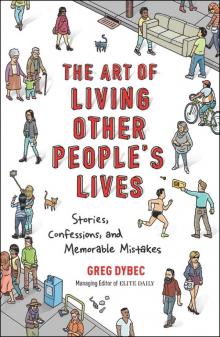

The Art of Living Other People's Lives Page 5

The Art of Living Other People's Lives Read online

Page 5

“You know,” she finally said, “this reminds me of when I was younger and would drive around rich neighborhoods during the holidays. The houses were always so beautifully decorated and I just assumed that the families inside were having a better Christmas than everyone else.”

In my mind I imagined a quiet suburban street lined with robust, two-story homes, decorated from top to bottom in lights as white as snow and wreaths the size of truck tires. I pictured thick smoke rising from the tops of chimneys and shiny, plastic reindeer grazing motionless on front lawns next to winding driveways overflowing with European sports cars. But behind the elaborate display worth at least a thousand Instagram likes, there was nothing. No laughter-filled dinners and borderline food fights. No watching the same Christmas movie for the thousandth time because it was tradition. No gifts under the tree that were purchased with any true consideration. And certainly no mothers who had become hashtag sluts for the sake of their children.

The Uber Diaries

I recently had a conversation with an Uber driver that went something like this:

DRIVER. You are very good at Uber.

ME. What do you mean? You’re the driver, not me.

DRIVER. You have five-star rating. You are VIP customer.

ME. That’s amazing. What does that mean exactly?

DRIVER. Every driver rated you five out of five. You are the perfect customer. You give no problems.

ME. That’s great. I’ve never had a bad experience with Uber. I use it all the time. In fact, I may be addicted to it.

DRIVER. It’s a pleasure to drive you, sir.

I looked down at the open Uber app on my phone, which told me my driver’s name was Vural and that he had a rating of 4.8 stars out of five. As far as I knew, there was no way to view your rating as a customer, so it was the first time I was hearing about my apparently flawless record. The conversation went on in similar fashion for the remainder of the ride. Vural couldn’t seem to get over the fact he was speaking with a five-star customer. I felt like a unicorn in his backseat, and he treated me as such.

Vural explained how he had journeyed from Turkey to New York City more than twenty years ago, and that driving for Uber allowed him to finally be his own boss. He had two small daughters and a wife at home. Before he was an Uber driver he was struggling as a taxi driver and, as he put it, doing some things he wasn’t so proud of. I didn’t push for details.

“I have some bad customers, some good customers,” he said. “But you, my friend, are the very best. I will rate you five stars and keep you perfect.”

This remark was strange for a couple of reasons. Firstly, my perfect rating was in the hands of a complete stranger. What if he’d been having a bad day and only rated me four stars? What if he was like one of those college professors who doesn’t believe in perfect and abides by the “A+ is a myth” mentality? Secondly, it was hard to imagine I was providing the most intriguing and cordial conversation he’d ever had with a customer. Was I only the best because I had a five-star rating already? He didn’t really get to know me before determining I was the best. If I hadn’t entered his car with a five-star rating, would Vural even like me?

I tried to think back to all my previous Uber rides—there have been many, too many—and couldn’t think of a time I hadn’t given a driver five stars. It was the same routine each time. They’d pick me up, drop me at my destination, and when the ride was over I’d quickly slide my finger to the right, highlighting all the rating stars that appeared on my phone’s screen. Apparently my drivers had been doing the same.

While I’d never overthought the rating system, Uber itself had become an undeniable part of my life, falling somewhere between water and shelter on my priority list. The first time I used the touch-of-a-button car service I was stuck in the rain after a late night at the office. Every taxi that passed by was occupied. A friend from work had told me to download the Uber app earlier in the day but I never did. So under the cover of a deli awning I downloaded the app, entered my credit-card information, and requested a car. Within minutes, a brand new Honda Accord pulled up right in front of me. I looked over at a couple searching hopelessly for a cab across the street and climbed in, unsure whether or not I was going to be chopped up in tiny pieces and sold on the black market or delivered safely to my apartment.

Luckily, the latter happened, and since that first time I’ve become increasingly dependent on the ability to pull out my phone and have a car show up within minutes. This service is especially useful in New York City, where I don’t own a car and try to avoid the crowded subways at all costs, even if it means cringing over credit statements reminding me of my expensive new habit. I was most likely hooked on Uber so quickly because I am both a sucker for convenience and even more of a sucker for any opportunity to feel luxurious. This absolutely includes having a black Escalade pick me up, even if I’m just going a few blocks down the street or back to my apartment alone.

As I stepped out of Vural’s car in front of my apartment, he once again noted that he’d give me a five-star rating. I assured him I’d be doing the same and we shared our final good-byes. Once I was settled in my apartment I opened the Uber app and waited for the rating screen to pop up so I could give Vural his five stars and move on. Except the rating screen never appeared. I checked my inbox for the Uber receipt, which includes a link to the rating option, though the e-mail was nowhere to be found. I set my phone aside and figured the e-mail would come through eventually. As I continued on with my night, heating up food and washing some dishes, I couldn’t help but check my phone every two minutes. Then I was struck with the thought of Vural waiting anxiously for me to submit my rating. I imagined him checking his phone every few minutes as well, slowly losing all hope he had in humanity as he considered the possibility that a five-star customer wasn’t true to his word. If Vural went back to doing things he wasn’t proud of, the burden would be on me.

Even more concerning to me was the possibility Vural would reciprocate what he perceived as a slight by giving me a low rating. I wondered if most drivers waited for their ratings to come in before rating their customers, if that’s how the process even worked. I was suddenly enraged by the fact that my perfect rating, which I’d only found out about that night, could be tarnished due to a technical glitch. So I did something I’d never done before. I called an Uber driver after I’d already been dropped off.

Uber lists both the driver and passenger’s phone numbers within the app, though the contact information is only available during the duration of a ride. Luckily I’d called Vural before he’d picked me up to explain in detail which street corner I was standing on, so I still had his number in my phone. After two rings Vural picked up, his voice an excited chirp on the other end of the line.

“Mr. Perfect!” he exclaimed. “How are you?”

“Listen, Vural,” I frantically explained. “The Uber app never gave me the option to rate you. And I never got the receipt e-mailed, so I can’t rate you that way either.”

There was brief silence before Vural responded. “My friend,” he started, “you do not need to worry about a thing. Uber is very busy right now. You will get the e-mail in time.” His voice was calm and reassuring, like a grandparent you love or doctor you trust.

“You will be happy to know,” he continued, “I have already rated you five stars. You are perfect still.”

I thanked Vural and wished him a good night, which in reality meant a good life. The call ended and I felt a warm comfort consume me.

“Mr. Perfect,” I mumbled to myself, laughing.

If I’m being honest with myself, Vural telling me I had a five-star rating changed Uber for me forever. Before my encounter with Vural, Uber rides were peaceful. Even if I did use the service to feel like someone important with a personal driver, Uber rides were still a place where I was able to gather my thoughts and breathe after hectic workdays or relax on the way to a restaurant or event. After all, I was paying for that luxury of solit

ude and convenience you can’t find on the subway during rush hour. Knowing I had a five-star rating to protect transformed me into a different kind of passenger. A passenger desperate to impress and dazzle, not sit back and relax. Each Uber ride after Vural’s may as well have been a first date or audition for The Real World. In the back of every Uber, I was part myself and part whoever it was I thought the stranger in the front seat wanted me to be. If the driver had on a Yankees hat I’d complain about the previous night’s pitching or talk about how much I missed Jeter. If they had a picture of their kids on the dashboard I’d pretend like I was thinking about becoming a father. It wasn’t dishonesty as much as it was being a good conversationalist. This led to more intimate conversations with strangers than I expected.

I began keeping notes on particular rides once I realized just how open some of the drivers were willing to be once they knew I was interested in hearing what they had to say. I also assume Uber customers are generally split between two demographics: the ones who say hello then sit quietly on their phones, and the drunk customers, who sync their shitty playlists with the car radio, talk about vulgar sexual experiences with their friends, and ask the driver to stop at McDonald’s for late-night Big Macs and milkshakes. A lot of these drunken customers probably throw up in the back of the car, too. I only did this once, but luckily someone else had ordered the Uber, so my rating wasn’t affected after blowing chunks out the window, but really all over the outside of the car. Some of the most memorable conversations with my drivers are the following, which have been partly transcribed to best reflect the original dialogue.

The Cheating Husband

It’s safe to say I may be the only person in New York City, or perhaps the world, who has witnessed their Uber driver cry. It wasn’t a heavy flowing cry with sobs and dripping snot, but there were tears and one definitive sniffle.

The ride started out normal. I got picked up on a Wednesday night from the same spot I get picked up every Wednesday night after playing basketball with a bunch of guys from Elite Daily. My driver was particularly quiet, and it worried me that sitting silent in the backseat could lead to an average rating, like four stars. Not a bad rating, but not perfect. You never know exactly what a driver’s rubric is.

I broke the silence by asking him how his night was going. He took his time to find the words, and then responded, “The night gives you too much time to think.” Just like that it was the darkest, most personal Uber ride I’d ever been on. Not to mention, he delivered the line with such conviction and honesty that if I remember correctly, I felt the hair on my arms stand up.

Imagine Dylan Thomas driving you around New York City while reciting,

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

I’m not one of those people who are good at memorizing quotes. I wish I were. I respect the people who can, at the drop of a hat, recall a sentence so perfectly architected and considered by someone historical and great and use it in everyday conversation. Though, there is one Van Gogh quote that I’d always remembered but never used. Finally, my time had come.

I swallowed, and with a shaky, completely unconfident voice, squeaked out the words, “‘I often think that the night is more alive and richly colored than the day.’ Vincent Van Gogh said that. You know, the painter.”

The driver remained silent, possibly considering the message, possibly ignoring me altogether. After successfully merging onto the entrance to the Queensboro Bridge, he spoke up.

DRIVER. Tonight is the night I will tell my wife I have failed her.

ME. [after taking at least ten seconds to process what I’d heard] What happened?

DRIVER. [after taking at least ten seconds to carefully search for the answer to my question] I will tell my wife of twenty-one years that I have been unfaithful.

[Okay, just assume there was at least a ten-second delay between each response.]

ME. Maybe she will understand.

DRIVER. She will understand what is true. That I am no longer the man she married.

ME. You’re strong for telling her.

DRIVER. I am the weakest I’ve ever been.

Through the silent pauses I could hear his muffled sobs. I decided to give the conversation a rest and let him be. As we moved slowly over the unusually crowded bridge, the Manhattan skyline stood tall and shimmering off to our right, a home to so many secrets.

The Conspiracy Theorist

After getting picked up at the airport I noticed the book Behold a Pale White Horse on my driver’s dashboard. The book is basically any conspiracy theorist’s bible, written by Milton William Cooper, an alleged ex-military man who claimed he had evidence of a number of government cover-ups, from HIV and AIDS being a man-made illness to the truth about extraterrestrials. More specifically, he claimed John F. Kennedy was assassinated because he was about to tell America that aliens were taking over the world. Cooper was killed in 2001 after shooting a police officer in the head. Ever since his book’s release, he had claimed the government was after him.

I asked my driver how he liked the book, telling him I’d always been interested in checking it out. He turned toward me with a look of anguish, his face like a balloon fighting the urge to pop, his foot still pressing down on the gas pedal.

“Can I tell you something?” he asked. “Like really tell you something?”

“Sure,” I replied.

The bulk of the conversation went something like this:

DRIVER. Do you know much about this stuff? You know, the Illuminati, government cover-ups? That kind of stuff.

ME. I’ve heard things.

DRIVER. I’ve been probing deep, man. Too deep I think. Last week I heard this weird noise on the phone while I was talking to a friend. I googled the sound afterward and it fit the description of a wiretap.

ME. Who do you think would be listening in on your calls?

DRIVER. Who do you think? The government. The American government. The Mexican government. It doesn’t matter, man. They’re all connected anyway. You know, they’re all working to form one universal government with one currency. That’s what I was telling my friend about on the phone.

ME. Like the New World Order conspiracy?

DRIVER. If you want to call it a conspiracy. Look, I know there are some crazy people out there, but I only focus on facts. You know there’s fluoride in the water we drink, right? That’s a fact.

ME. I guess so.

DRIVER. Well there is. There’s fluoride in the water we drink, and do you know what fluoride does to us?

ME. I’m not exactly sure.

DRIVER. It’s like poison to a specific part of our brain. The pineal gland, which is the part of our brain that allows us to connect with spiritual dimensions and think at a higher level. It’s our third eye. The right dose of daily fluoride actually shrinks the gland and calcifies it, and when it shrinks, we become more submissive and don’t question things. We just do what we’re told. How do you explain that?

I’d witnessed firsthand the effects that diving too deep into conspiracy theories can have on a person. An old roommate of mine had also read Behold a Pale White Horse and watched every conspiracy video on YouTube known to man. It got to a point in which I couldn’t even watch television without his pointing out every triangle that represented the Illuminati and demonic symbol that an untrained eye wouldn’t notice. Once he physically had to leave the room because of how satanically charged an AT&T commercial was.

Granted, a lot has gone unanswered in this swelling, sinister world of ours. A lot of government cover-ups and global scandals have been uncovered. But it seems to slightly defeat the purpose of a valid conspiracy when someone believes in all the possibilities. Is it the aliens or the freemasons pulling the strings? The Illuminati or the devil? Are they all at a round table somewhere hoarding Cuban cigars and face-timing Beyoncé?

If it were a normal, c

asual conversation I were having, I’d happily play devil’s advocate and mention that there are potential benefits to fluoride in water and that global governance seems highly unlikely. Though, this wasn’t a normal conversation. This was an Uber ride, and I couldn’t risk damaging my five-star rating because the driver sensed my doubt that the world was one big rotating lie in an unexplored universe. So instead of questioning his rationale, I nodded in agreement.

“It makes a lot of sense when you put it that way,” I told him.

He spent the remainder of the ride rattling off videos for me to watch and articles to read. We idled in front of my apartment for about ten minutes so he could finish explaining the reptilian theory, which is the belief that the world is actually controlled by shape-shifting reptiles that took the form of humans and gained full political power.

“That last theory is a little out there,” he admitted. “But you just never know. You really just never know.”

The Slow Driver

The only time I ever considered not rating a driver five stars was one morning when I had an early flight to catch. The Uber picked me up at my apartment and I expressed I was running a bit behind schedule and needed to hurry to the airport. I should have jumped out of the Uber and called another one the moment my driver began talking about the newly enforced speed limits in New York City, which required twenty-five miles per hour on any normal roads and forty miles per hour on highways. Of course, I respect the laws and especially any rules that facilitate personal safety, but the fact of the matter is nobody actually drives forty miles per hour on a highway. In fact, it seems unsafe to drive at such low speeds while everyone around you is going at least double the speed limit.

The Art of Living Other People's Lives

The Art of Living Other People's Lives