- Home

- Greg Dybec

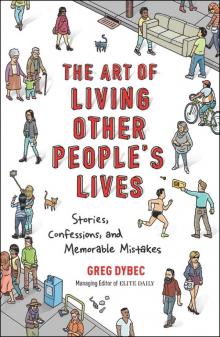

The Art of Living Other People's Lives Page 2

The Art of Living Other People's Lives Read online

Page 2

When a girl says sure what does it mean

Do women love men with belly

Am I a bad kisser

Can’t get my girl to cuddle me

I like wearing socks during sex why?

Are guys without girlfriends useless

Boyfriend distant

How to keep your girl happy with words

Everyone else is getting married

Wife not adventurous with sex

I always get drunk and regret it

I felt more connected with the vast Internet population than ever before. Each day I’d wake up to a stream of strangers’ most important life questions and concerns. It was like knowing the plots to countless movies but never being able to see the ending. I’d go through the day wondering whether that guy ended up getting his girlfriend to cuddle. Did the person who cheated end up cheating again? Did their partner find out?

If there’s a lesson in any of this, it’s that you are not alone, good people of the Internet. I saw so many questions repeated countless times, the most frequent (perhaps unsurprisingly) being those about sex, love, and family. We’re all asking the same questions at some point in our lives, and there is something genuinely comforting in that.

Of course, you can have too much of a seemingly good thing. I was working from home the day it occurred to me that perhaps I’d taken advantage of the keyword feature’s purpose. The truth is I’d gone a little too hard the night before, which happened to be a Tuesday. (Fun fact: Finishing a full bottle of sake by yourself pretty much guarantees you’ll be working from home the following day.) After sleeping through my alarm, I logged online around 10 a.m., still too dizzy to pour my dehydrated self a glass of water. About twenty minutes into trying to get work done, I realized I’d be kidding myself if I thought it’d be a productive day. So I logged on to Google Analytics and headed straight to the keyword searches. At least it was sort of work related.

Through the haze of my hangover, I scanned the familiar list as it refreshed every few seconds. After a few refreshes I noticed a couple of distinctively somber searches. They especially stood out within the mix of the more common “how to give a blow-job” and “when to ask her out” questions.

Within seconds of one another I came across the following searches:

I hate people

Alone in the world

I was experiencing one of those overly dramatic hangovers in which you consider everything you’ve done in your life and whether it’s all been worthwhile, so those searches hit me hard. I’d logged on to be cheered up by strangers of the Internet, not depressed by them. More than that, though, I had a hard time believing these heartbreakingly honest searches were a sudden, new trend. I’d never noticed questions like them, though. It occurred to me that I’d never really watched the searches unfold for long periods of time. I mostly just popped in and out throughout the day to grab a screenshot or two. It’s possible that I’d conditioned myself to see what I wanted to see, collecting not the full spectrum of searches, but whatever pleased my mood. When I hoped to find funny sex questions, it seemed like there was an abundance of funny sex questions. When I was on the prowl for poetic confessions like “Can you fall in love through texts,” the supply seemed endless.

Since there was no chance of my moving from the couch, I decided I’d keep an eye on the searches. Throughout the next couple of hours, there was mostly a stream of the usual types of questions about love and sex and how to save money, though in between those, I pulled out “Feeling depressed need help,” “Is it normal to constantly plan for death,” and “Why did my mother have to die.”

Combined with my pounding headache and a lingering taste of acidic regret drying out my mouth, the searches only made me feel worse. Throughout the rest of the day I collected:

Trust issues with abusive mom

Husband is quiet and distant

Am I in love with someone I can never have

He will never love me back

Is there a point in living if she doesn’t love me back

When you find out your man is cheating

I hate meeting people

Why do I think about suicide

Don’t belong in my family

Doubt that people love me

When I was young I’d go camping every year with my dad and brother. We’d usually spend long weekends at a campground in Upstate New York, fishing during the day, sitting around a fire at night, and sleeping on the uneven ground in a tent. On most nights, my dad would want to go for a walk to get a better view of the stars. The walks always enticed me as much as they frightened me, mostly because the darkness that enveloped the campground at night was unlike any darkness I’d known before. It was thick and had weight to it. Anything could have been hiding in that darkness and you’d never know. I was always conflicted during those walks. I wanted to use my flashlight, but at the same time, shining the light into the woods around us meant the possibility of revealing something I didn’t want to see. At that age, a bustling imagination enhances the fear of the unknown. That fear usually resulted in my walking closely by my dad’s side, following the single stream of light from his flashlight that illuminated the path ahead. It felt safe to let the darkness play its role, to let whatever was concealed by it stay that way.

By the end of the day, as my hangover was finally beginning to wind down, I felt like I’d been shining my flashlight places I shouldn’t have. I’d always sensed that perhaps I was overstepping a boundary by taking pleasure in the private thoughts of others, and that fateful day proved my theory to be correct. Yes, nothing you do on the Internet is private, but I doubt people assume that means a twenty-five-year-old in Queens is collecting their most intimate thoughts in a folder on his MacBook. Regardless of the fact I didn’t know who they were, a part of me was still finding joy in their genuine struggles. And clearly the searches weren’t only coming from teens wondering how to hold hands and cuddle their girlfriends. They were from a range of people who had lost loved ones, were fighting depression, and were simply trying as hard as the rest of us to figure out their purpose in this sometimes lonely life.

I decided to give up the keywords feature cold turkey. I made a hungover vow to myself to let strangers’ deep, personal Google searches float around the Internet cosmos without my interference. Besides, rather than spy on countless Elite Daily readers, I could do my actual job and make sure the site remained relevant.

If my admittedly strange obsession with reading the private thoughts of others had taught me anything, it’s that we’re all trying to cope with what life throws at us, whether it’s good, bad, or somewhere in between. We’re all asking ourselves questions we’d never ask out loud. The woman passing you by may be trying to figure out why her husband has been acting so distant. That woman who ruined your day by accidentally stepping on your new shoes could have just lost someone she loved. The guy sitting across from you could very well have a corkscrew penis.

During my morning commute, when I’m surrounded by tired-looking faces and people preparing for another day, I can only imagine the range of questions that a single subway car would yield if they were to appear on my computer screen. Now when I make eye contact with a stranger across a train car, I don’t see them as a statistic. I don’t even create fictional stories about them and their interests. I just smile to myself, finding comfort in the fact that the Internet is there for them, in all its anonymous and nonjudgmental glory.

Translation

I was thirty thousand feet in the air and halfway to Italy for a two-week trip with my family when the panic set in. It was the same panic I experience almost every time I travel internationally. It has nothing to do with turbulence and crying babies and everything to do with the fact that in a few short hours I’ll be in a country that speaks an entirely different language from my own.

I gave up on my dream of learning another language a long time ago. For some reason, capturing even the basic phonetics of any foreign dialect is impossible for me,

no matter how often I practice in the shower. Even pronouncing the names of wines has proven too difficult, so much so that I find myself ordering whatever’s easiest to say out loud at restaurants and not what I actually want to drink. Despite all of this, I actually travel often, for both work and pleasure, so there’s never a shortage of anxiety and embarrassment.

Surprisingly, I can recall a decent number of Spanish phrases from my high-school classes. The words even sound fluent when I say them in my head. But then I open my mouth and suddenly I’m yelling like a drunken game-show host, adding unnecessary emphasis to words in a voice much deeper than the one I use to speak English. I first realized this in Barcelona, when I asked a street vendor “Cuanto dinero?” for a pair of sunglasses and came off like I was announcing he’d just won a brand new car.

In Paris, I got by by mumbling “bonjour” and “merci” while walking as quickly as possible in the opposite direction of whomever I was spewing sound at. I got so good at the walk-and-talk that locals and cashiers started calling after me in French to strike up conversations, assuming, I imagine, that someone in such a hurry couldn’t possibly be a tourist. In South Africa, people were prepared to perform the Heimlich maneuver on me when I attempted to pronounce “goeie môre,” which is Afrikaans for good morning. In Brazil, my “obrigado” rolled off my tongue with an embarrassing bravado that sounded nothing like Portuguese and more like an exaggerated line from an Italian mob boss in The Godfather. One time in Belize, a tour guide tried to teach me how to properly enunciate the phrase, “Me belly full,” which is a way to suggest “I’ve had enough to eat” in Belizean Creole. What should have resembled an accent similar to Jamaican Patois squeaked out of me the way I imagine leprechauns sing.

Now when I travel, I’m fine up until the point the trip starts to feel real, which is around the same time I realize I can’t fall asleep on the plane or a flight attendant crushes my elbow with a beverage cart. Then the fear of embarrassing myself takes over, and suddenly the trip I’d been anticipating becomes the trip I’m dreading.

I realized midflight that Italy was intimidating me more than any other country I’d been to, mostly because I’ve spent the majority of my life in America telling people I’m Italian. Americans love to ask anyone and everyone “what they are,” even when they know that person’s ancestry has played little to no part in their upbringing. My answer to this question has always been, “I’m mostly Italian.” I’m Italian only on my mother’s side, but her family is more than double the size of my father’s, so I grew up eating pasta on Sundays and hearing stories about my great-grandmother cutting the heads off live chickens in the kitchen. That’s Italian enough for me. Or at least in America it is.

Being of Italian descent in America, like being of any ethnic descent in America, doesn’t automatically mean you’ve lived some wildly different life than anyone else around you. Unless you’re first or maybe second generation, odds are you grew up similarly to the people around you who were the same age. Other than the selection of home-cooked meals and the religion my parents raised me in, my childhood wasn’t all that different than the Puerto Rican kids down the road or the Jewish kid across the street.

Of the people I’ve met whose answer to the “what are you” question is also an apprehensive “Italian,” most don’t speak any Italian in their homes or have family members living in Italy. For many, being Italian in America is an excuse to buy meats from a privately owned deli with a name like Roscoe’s or Carmine’s Pork Store, because supermarkets can’t possibly import their sausage and salami the same way. The closest my family comes to speaking Italian is pronouncing the names of foods in illogical ways. Mozzarella is “mutts-a-dell,” prosciutto somehow becomes “bro-shoot,” and gnocchi is a completely new word each time.

In 2009, the reality of being a modern-day Italian American was exploited and exaggerated on the show Jersey Shore, and on all the embarrassing seasons and spin-offs that followed. Suddenly being Italian American was like being in an artificially tan, gym-worshipping, vodka-guzzling cult. The problem was that the show’s participants truly believed, or were paid to truly believe, that attributes like loyalty, hospitality, and friendship were strictly reserved for Italian Americans—as if they weren’t familial and even basic human traits. Perhaps that’s the beauty of the confused Italian American clan: they take genuine pride in and ownership of characteristics that are universal.

Most likely, the show was just a last stand to depict the average white American as something cooler and more exotic than your average white American. In turn, white people became that much more uncool and infinitely less exotic.

For me, traveling to Italy meant finally experiencing the culture I’d half-assed and blindly considered my own. I turned to my brother, Cole, and proposed we pretend to be Dutch or English, even though he was in honors Italian in high school at the time. We even brushed up on what we remembered from sign-language classes we’d taken. Anything to avoid being exposed as the pasta-eating frauds we felt we were.

When we finally landed and ventured out in Rome, not attempting to speak Italian was easy. Like most big cities around the world, there are so many tourists and transplants that it’s easier if everyone just uses broken English. Even Americans use broken English when traveling abroad. We can’t help but shout fragmented sentences like “Pizza, how much?” and “Bathroom? Toilet? Where?” Things just seem more efficient this way. And as long as you’re adequately apologetic and defeated, the Romans are cool with it, too.

My mother, whose maiden name is Visceglia and whose ancestors hail from Bari, a small coastal town in southern Italy, had been planning this great return to the motherland for some time. It was the kind of vacation that a family talks about for so many years that it seems like it’s never going to happen, until one day it just does. The kind of vacation for which people cash in years’ worth of saved-up coins.

From Rome we traveled to Florence and from Florence to Siena. We moved quickly through each city, taking in the sights, filling up on carbohydrates, and staring at gelato behind glass as if each flavor were a relic from Jesus’s childhood laid out neatly on display. Like in Rome, we defaulted to English, minus my mother’s few painful attempts at “grazie.” She spent a full year prior to the trip listening to Italian language-learning audio guides in her car, but somehow her limited vocabulary sounded more like Arabic than anything else. It’s clear whose genes I got in the foreign-language department. After enough glasses of wine my father would resort to the Spanish he knew, throwing out “gracias” left and right and, I’m pretty sure, an “adios” or two. Cole refused to speak a word of Italian, despite my mother’s insistent requests. I opened my mouth only to eat.

We spent a full week hopping from city to city, and the plan for the second week was to rent a car and head to the mountains, away from the bustling tourism. My mother’s dream had always been to spend a week in a villa in Tuscany . . . or it had at least been her dream since seeing the movie Under the Tuscan Sun. Something tells me a lot of middle-aged women have the same dream, but good for her for acting on it. The only difference is most women probably dream of leaving their husbands then traveling to a villa in Italy. Good for her for not acting on that.

The deeper into the mountains we drove, the less English the locals spoke. Somewhere along the way to Caprese Michelangelo, where the villa was located, we took a wrong turn onto a narrow, cobblestoned road and our car ended up in a dead-end alley. When we rolled down the window and asked three older ladies passing by if they could help us with directions, they looked at us in awe, as if our car were a spaceship and they were the first humans to make contact with extraterrestrials. More likely, we were the first English speakers to ever make it that far into the mountains.

Thanks to some crafty maneuvering, we eventually got the car out of the alley and continued up the terrifying and steep mountain roads toward the villa. There weren’t many homes or people along the way, just a few scattered churches and end

less green fields. It turns out Caprese Michelangelo was the birthplace of the artist Michelangelo. I stared out the window on the way up the mountain, trying to see where his inspiration may have come from, while at the same time praying we didn’t hit a turn too fast that would send us plummeting to our deaths.

Thankfully, we made it to our destination in one piece. As we inched our way up the winding driveway, I was surprised by the villa’s modest stature and underwhelming appearance. It’s not that the place wasn’t nice, but there’s definitely a certain expectation attached to the word villa. The word calls to mind images of luxury and wealth. A villa, in my mind, was a place where rich people go to feel even richer without having to interact with humans other than the ones they handpick.

About twenty cats were waiting outside upon our arrival, like some sort of mangy welcome brigade. They all took turns rubbing their alarmingly skinny bodies against our legs as we made our way to the front door and wondered if Italian cats had fleas. We had to squeeze through the door one by one to make sure none of the emaciated animals made it into the house. Once we were all inside we dropped our bags, turned to each other while letting out a sigh of relief, then simultaneously asked, “What is that smell?”

The entire place smelled like death, or shit, or someone who took a shit all over the place before dying. It didn’t take long to figure out it was coming from the nearest bathroom—it was impossible to get close to the door without gagging. It was as if Michelangelo himself had taken a dump and forgotten to flush, and we were the first people in history to stumble upon it.

I looked at my mother, her shirt over her nose, eyes teary from the stench, and wondered if her dream of a pleasant Italian villa was already tarnished. Then there was a knock at the door. It was the woman we’d rented the house from. Her name was Marianella and she lived with her family in a small house no more than two hundred feet from our villa. They owned the entire property. Aside from the villa and their house, there was a tiny, rundown church and a fully functioning farm on the premises, complete with cows, sheep, roosters, pigs, and a barn, all no more than a short walk away. Rome and Florence and all the other busy cities with their McDonald’s restaurants and broken English and lines for museums felt like they were on the opposite side of the world. We were farm people now, with a bathroom that reeked of the apocalypse and twenty starving cats waiting outside our front door.

The Art of Living Other People's Lives

The Art of Living Other People's Lives